Unless by lived experience, it’s impossible to step in the shoes of someone diagnosed with a rare cancer. It might be something like waking up on an island no one’s ever heard of and searching for a map. Forged together by circumstance, you wander with others sharing your diagnosis, searching for answers, looking for directions.

“My life is divided into two parts: before and after diagnosis,” says Jackie Herman, an Ontarian living with neuroendocrine cancer – a rare, but on-the-rise cancer that can manifest almost anywhere in the body.

In 2008, Jackie’s family doctor ordered an ultrasound in response to her gastrointestinal issues. Spots on her liver led to a referral to a liver transplant surgeon at Toronto General Hospital, who, during her first visit, identified them as metastatic neuroendocrine tumours.

“It was very frightening, with the largest tumour being five or six centimetres. I can't remember exactly, but my liver was riddled with tumors, at 38 years old. You're asking yourself, what is going to happen to me? How did this happen?” she says. “And it's such an unknown cancer. I didn't get much information from my doctor. I was left to my own devices to research, which I did. Prior to that, I had never read any kind of medical research paper in my life.”

Seeing her struggle, Jackie’s husband encouraged her to attend a support group offered by the Canadian Neuroendocrine Tumour Society (CNETS), as recommended by her endocrinologist.

“I kept saying no, I don't want to sit around with other cancer patients. It's going to be depressing and really sad,” Jackie says.

But he persisted, and eventually, Jackie showed up to a meeting. “It was the best decision I ever made,” she says. “I saw so many people that, you'd have no idea what's going on inside their bodies. Because on the outside, they look pretty good – they're not going through chemotherapy and losing their hair. They're not particularly losing weight. It depends on the stage of their disease, obviously, where they're at. But the majority are not. I saw people who looked so healthy. And they had been living for a number of years. It was just amazing.”

That was in 2009, and Jackie has been connected to CNETS ever since, for the last nine years, as president of the board of directors. A patient, activist, and leader within the neuroendocrine cancer community, these experiences are part of Jackie’s foundation.

ABOUT NEUROENDOCRINE CANCER

It took the lives of Steve Jobs and Aretha Franklin, but it’s not widely discussed or understood.

Neuroendocrine cancer forces us to abandon the narrative that cancer is associated with the organ where it is found and instead consider the cell within which it originates.

Neuroendocrine cells live throughout the body and play critical roles in a number of bodily functions due to their ability to release hormones that coordinate physiological processes needed for life.

“You can have this cancer in almost any of your soft tissues. On your skin. On your adrenal glands. Your pancreas, anywhere along your intestines, liver, ovaries, breasts – everywhere,” says Jackie.

“And these tumours can all have their own personalities depending on where they start from and whether or not they produce excess hormones. They can behave differently in different people,” says Dr. Daniel Rayson, head of oncology and chair of the Neuroendocrine Tumor team at the QEII Health Sciences Centre in Halifax, Nova Scotia. “No two cases are completely alike.”

To complicate things further, NETs mimic other illnesses with a long list of possible diagnoses and can cause symptoms such as fatigue, impaired breathing, diarrhea, abdominal pain, hypertension and skin rashes to name a few common examples.

That – combined with a lack of accurate diagnostic tools available in Canada until recently – is part of the reason people stay sick so long, as told by Sharon Needham, neuroendocrine patient and face of the QEII Foundation’s recent fundraising campaign, who was ill and misdiagnosed for more than seven years.

And while every journey is different – and aggressive forms exist – many patients can live with neuroendocrine cancer for years.

JACKIE’S JOURNEY AND CARE TODAY

Jackie’s diagnosis experience was unusual, as many neuroendocrine cancer patients see doctor after doctor and go years without answers.

“That didn’t happen to me. My diagnosis was quick, but in retrospect, I had symptoms for years,” Jackie says. “I just didn’t make the connection.”

Jackie had 60 per cent of her liver removed in 2008 – and additional tumours removed in 2016.

She estimates that today she lives with a dozen tumors on her liver – but doesn’t know for sure.

“I’ve had disease in my liver for all these years, but that’s not what concerns me most. What I need to know is when there is new disease outside my liver. I’ve never felt confident that it’s being fully monitored.. I can have a chest CT or an abdominal MRI, but is there disease anywhere else? I know from first-hand experience that it’s possible,” she says.

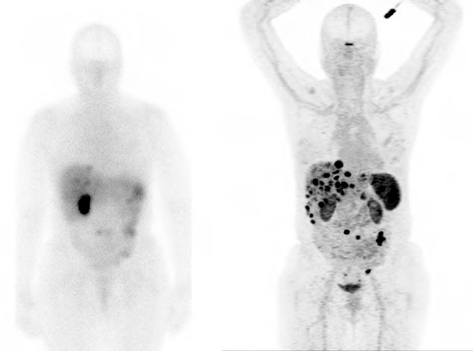

The standard scan used in Canadian hospitals today involves a radioactive tracer called indium-111 octreotide that is injected into the patient and can show neuroendocrine tumors in the body. It leaves much to be desired and often must combined with other tests – such as CTs and MRIs to get an accurate and complete picture.

It isn’t nearly as accurate as what medical science can offer today – in the form of a world-leading tracer called gallium-68 DOTATATE.

In 2015, Jackie entered a clinical trial at an American hospital, where she would first access a gallium-68 PET-CT scan. For the first time, she received a clear image of the cancer in her body – a peace of mind that couldn’t be offered at home.

ACCESS AND ADVOCACY IN CANADA

Imagine having to live with a disease that you couldn’t receive proper monitoring for. As QEII patient Sharon Needham frankly described it, “it’s like not being able to receive my mammogram if I had breast cancer.”

In Canada, gallium-68 DOTATATE scans have largely been accessed through clinical trials, such as a trial hosted in Sherbrooke, Quebec – a centre that spearheaded such trials – and is still the only clinical trial of its kind that accepts out-of-province patients, including both Sharon and Jackie.

Finally, thanks to champions who have long advocated for change, like Jackie and CNETS, and medical experts, including our own QEII teams – this struggle will start to come to an end.

Gallium-68 DOTATATE was approved by Health Canada in 2019.

And the QEII Health Sciences Centre will be among the first to offer this diagnostic scan to its patients, with the support of donors who have been called to support this urgent need, with a campaign close date of March 31.

The QEII’s Dr. Daniel Rayson and Dr. Steve Burrell, head of nuclear medicine, are at the forefront of this work, to offer the best neuroendocrine cancer care locally to their patients.

“This is going to have a major impact on patients” says Dr. Rayson, “not only in terms of monitoring disease, but for treatment selection.”

“It is, for me personally, probably the most gratifying issue in my career that we worked on together as a team and it’s actually happening,” says Dr. Burrell.

In addition to the immediate impact felt by patients and their families, as more health centres across Canada acquire gallium-68 DOTATATE, it allows them to conduct research and push medicine forward in terms of new treatments.

“It allows us to participate in multicenter, cutting-edge clinical trials that aim to develop new treatment strategies,” says Dr. Rayson.

HOLDING ONTO A BRIGHTER FUTURE

While you can hear the fire in Jackie’s voice upon speaking with her, she lives with daily fatigue. Along with skin flushing and digestive issues, she faces cognitive impairment, including memory loss.

The combination resulted in her inability to continue working.

But she hasn’t lost hope that things will get better for people like her.

“Dr. Rayson is absolutely phenomenal in his advocacy for his patients. We need a lot more champions like him,” Jackie says. “With Health Canada approval, hopefully we will start to see gallium-68 DOTATATE as standard care and part of hospital budgets.”

In the interim, many patients across Canada, like Jackie, are living life in the unknown. And it’s a tough place to be.

Jackie is a patient at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto. While a clinical trial is available there, the requirements of the study restrict the number of scans patients can receive. .

And while advocacy pays off, as we are starting to see locally in Halifax, it takes years, and can wear on individuals living at the forefront of this fight.

“You ask yourself why,” Jackie says. “Is it because we live longer periods of time? And so we're not considered as dire as, you know, other types of cancers that are more aggressive? I don't know the answers to these questions yet.”

“It might be a combination of all of that. But neuroendocrine cancer patients deserve to have access to the best diagnostics, the best care, just like every other patient.”

Thank you to QEII Foundation donors who continue to support this urgent need in cancer care on behalf of Atlantic Canadians. Those living with neuroendocrine cancers will soon access world-class scanning locally, with gallium-68 DOTATATE at the QEII.

To learn more about the QEII Foundation campaign to bring gallium-68 DOTATATE to the QEII or to donate, visit: QE2Foundation.ca/gallium.

To learn more about the Canadian Neuroendocrine Tumour Society, visit CNETS.ca.